Introduction:

Trademarks are generally words, logos, symbols, and phrases used in business to identify and differentiate the goods of one company or manufacturer from those of another and to specify the source of the goods. For instance, the trademark ‘Nike’, together with its logo ‘swoosh,’ represents the shoes manufactured by Nike and differentiates them from shoes made by other brands (like Reebok or Adidas).

Besides, sounds, shapes, colors, and fragrances too can be registered as trademarks. In some situations, protection of trademark may pull out ahead of symbols, phrases, and words to embrace added features of a product, like its packaging or its color. For instance, the distinctive shape of a Coca-Cola bottle or the pink color of Owens-Corning fiberglass insulation may possibly serve as an identifying feature. These types of features usually come under the phrase ‘trade dress,’ and possibly are protected if customers relate that characteristic with a specific brand instead of the product in general. (USPTO, 2016)

Trademark law protects a company’s business identity or brand by daunting other companies from taking on a name, word, or logo that is confusingly alike to an existing trademark. Trademarks help customers to promptly identify the source of a certain product. For example, rather than inquiring a salesperson about the manufacturer of specific athletic shoes, customers can identify it by looking at a name, sign, or distinctive patterns on the shoe to know the brand/manufacturing company of the shoes. Besides, trademarks also provide the manufacturer the incentive of investing in its products’ quality like Apple provides innovative and high-quality products so a trademark on its products conveys the message to the consumers that the product is of fine quality. This will attract the customers to buy Apple products instead of buying any other brand. Trademark law promotes these purposes by regulating the proper use of trademarks.

Trademark Requirements:

A trademark needs to fulfill two fundamental requirements to make a mark eligible for trademark protection: These are:

- To use the Mark in Commerce: According to the Lanham Act, a trademark should be a mark that is aimed to be used in business activity and should be registered with PTO with a bona fide intention of using it in commerce. A mark that is registered with the PTO should be marked with the ® symbol. Registration for a trademark can be applied and even permitted if the applicant is able to provide a good, faithful written application of using the mark in business in the future, even if it is yet to be used. Under both, common law and Lanham Act registration procedures, special rights to a trademark are granted to the first to use it in commerce. Besides, registration with the PTO also provides the privilege (even if the mark is used in a limited region) to use the mark throughout the United States until and unless the mark is already used in any geographical region and even have the mark registered.

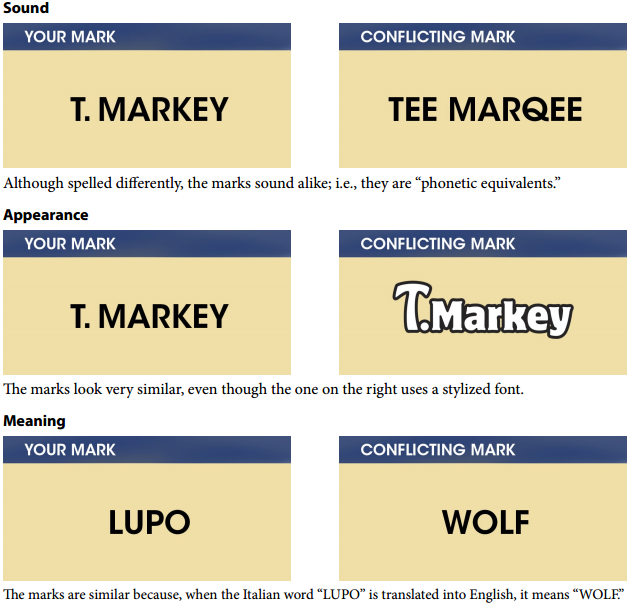

- It Must Be Distinctive: The second requirement for a mark to not been rejected by USPTO is that it should be different and should avoid the ‘likelihood of confusion between the proposed mark and an already existing registered trademark. Below are the examples of the likelihood of confusion:

Categories of Trademarks: What are not protected by trademark laws?

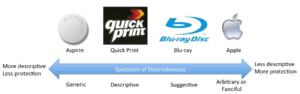

Trademarks are basically classified into four categories of distinctiveness:

- Arbitrary/Fanciful: Arbitrary/fanciful marks are the strongest and easily protectable types of marks as these marks have no rational connection to the underlying product. Fanciful marks are imaginary words having no dictionary or other known meanings (e.g. Audi), while arbitrary marks are real words having a known meaning but does not any association or relationship with the goods protected (e.g. Starbucks). These marks are register-able and, in fact, are more feasible to get registered than descriptive marks. Furthermore, as these kinds of marks are inventive and odd, the chances of having similar marks are less.

- Suggestive: A suggestive mark suggests or evokes an attribute of the original good. For instance, the word “Blu-Ray” is suggestive of a soft copy disc but does not particularly describe the original product. This makes suggestive marks intrinsically distinctive and is, therefore, given a high level of protection.

- Descriptive: A descriptive mark is a word, logo, design, or any other identity that directly describes a specific attribute or quality of the underlying product (like its color, function, odor, ingredients, or dimensions). For instance, “Oat Nut Bran Cereal”, “Pizza Hut,” and “Quick Print” are marks that describe the basic offering of the underlying product, that is, cereals, Pizza, and printing. As these descriptive marks are not inherently distinctive, therefore they are considered weak and are only registered by USPTO when they find the mark has acquired distinctiveness or “secondary meaning.”

- Generic: A generic mark describes the general category to which the intended product belongs. For instance, the word “Computer” is a generic term for computer equipment. Under the trademark law, these generic terms are not protected for the reason that they are basically too functional for classifying a specific product.

However, in cases, descriptive marks are eligible for protection and can be registered only after they have been able to attain secondary meaning. Therefore, for descriptive marks, there might be a time period following the initial use of the mark in business and prior to acquiring a secondary meaning, through which trademark protection is not granted. Once it has attained secondary meaning, trademark protection is approved. (LII, 2015)

History of US Trademark Law:

Trademarks are governed under both state and federal law. Initially, state common law offers the primary source of protection for trademarks. However, by 1870, the U.S. Congress passed the first federal trademark law. From that point forward, federal trademark law has constantly extended, greatly attaining the areas that were first controlled by state common law. The major federal law is the Lanham Act that was ratified in 1946 and latterly altered in 1996 (15 U.S.C. 1051–1127).

The Lanham Act gives the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) administrative rights of trademark registration. At the moment, federal law offers the key, and by large the most widespread source of trademark protection, even though state common law proceedings still exist.

The latest growth in U.S. trademark law includes the adoption of the Federal Trademark Dilution Act of 1995, the 1999 Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act, and the Trademark Dilution Revision Act of 2006.

Unregistered marks are also given Federal projection under Lanham Act 15 U.S.C. 1125(a) that creates a communal reason of action for claims of the false title of origin and copied promotion. Still, the registered marks under U.S. Patent and Trademark Office are given higher importance and degree of protection than the unregistered marks. Unregistered product trademarks should be marked with a “tm”, and unregistered service marks should be marked with an “sm” (WIPO, 2015).

Benefits of Registering TradeMarks

Although registration is not an obligation to federal trademark protection, registered marks benefit from noteworthy advantages over unregistered marks. These advantages include:

- Registration provides nationwide trademark rights and ownership of the mark

- A registered mark may attain an undeniable position after five years of incessant use, which improves the owner’s rights by eradicating numerous defenses to claim infringement.

- The registered owner is acknowledged to be the proper owner of the trademark rights

- The presupposition that the mark has not been discarded through non-use.

- Right of entry to Federal Courts for taking legal action regarding trademark infringement

- Constructive notice: states that the infringers do not have the right to claim that they were unconscious of a registered trademark.

- Propose a better cure for infringement, comprising the likelihood of triple damages and illegal punishment for counterfeit.

- The registered mark has the privilege of informing the U.S. Customs Service to stop others from introducing or importing goods having infringing marks.

Reasons for Rejection of Trademarks:

The PTO has the right to reject a registration on any number of justifications and the rejection of the mark does not always represent that it is not eligible for trademark protection; in fact, it at times states that the mark is not eligible to the supplementary benefits listed above. Apart from this many states in the United States also have their own registration systems beneath state trademark law. (Harms, 2014)

The applications for trademark registration are keenly inspected by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) under the assistance of the police, courts, and trademark registers. In case if the examiner rejects an application, the applicant is given a grace period of six months to respond or revise the application and afterward will be reexamined. The above-described procedure can possibly recur until either:

(a) The examiner issues an ultimate rejection of registration, or

(b) The applicant is failed to respond, revise or request for a time frame of six months.

In the case where the application for registration is accepted by an examiner, it is then published in the Official Gazette of the PTO for opponents. Any person can file an opposition whom he considers could damage because of the registration of a new mark. To prove his point an opposer should request and verify that:

(a) In what ways he/she is expected to be harmed by a registration of the applicant’s mark; and

(b) That there are valid official justifications he could present to prove why the applicant cannot be permitted to register the claimed mark.

During a period of five years following a trademark has been registered in the PTO, any owner who thinks that he/she is or will be debilitated by the registration has the authority to forward 3an appeal for termination of registration. (Tysver, 2015)

Under The Tariff Act of 1930, it is considered illegal to import any goods of foreign manufacture into the United States if such goods or their packaging possesses a trademark already have by a U.S. national, corporation or other institutions and its trademark is also registered in the PTO.

Trademark Rights Can Be Lost:

If the use of a trademark is certified exclusive of satisfactory quality control or management by the trademark owner, the trademark will be canceled. And if the rights to a trademark are allotted to another party in gross, without the corresponding sale of any assets, the trademark will be canceled. The rationale for these rules is that, under these situations, the trademark no longer serves its purpose of identifying the goods of a particular provider. Genericity is when a trademark loses its distinctiveness over time and becomes generic, thereby losing its trademark protection. Trademark rights must be maintained through actual lawful use of the mark for a period of time, which varies, or rights to the mark will cease. In deciding whether a term is generic, courts will often look to dictionary definitions, the use of the term in newspapers and magazines, and any evidence of attempts by the trademark owner to police its mark.

In addition, if a mark’s registered owner(s) fails to enforce the registration in the event of infringement, it may also expose the registration to become liable for an application for removal from the register after a certain period of time on the grounds of “non-use”.

Trademark Infringement

Trademark infringement occurs when one party adopts or uses a trademark that is confusingly similar to the prior adopted and used trademark for similar products or services. In deciding whether consumers are likely to be confused, the courts will typically look to a number of factors, including:

(1) The strength of the mark;

(2) The proximity of the goods;

(3) The similarity of the marks;

(4) Evidence of actual confusion;

(5) The similarity of marketing channels used;

(6) The degree of caution exercised by the typical purchaser;

(7) The defendant’s intent.

Using a very similar mark on the same product may also give rise to a claim of infringement, if the marks are close enough in sound, appearance, or meaning so as to cause confusion.

Trademark Dilution

In addition to bringing an action for infringement, owners of trademarks can also bring an action for trademark dilution under either federal or state law. Under federal law, a dilution claim can be brought only if the mark is “famous.” In deciding whether a mark is famous, the courts will look to the following factors: (1) the degree of inherent or acquired distinctiveness; (2) the duration and extent of use; (3) the amount of advertising and publicity; (4) the geographic extent of the market; (5) the channels of trade; (6) the degree of recognition in trading areas; (7) any use of similar marks by third parties; (8) whether the mark is registered. Kodak, Exxon, and Xerox are all examples of famous marks. Under state law, a mark need not be famous in order to give rise to a dilution claim. Instead, dilution is available if: (1) the mark has “selling power” or, in other words, a distinctive quality; and (2) the two marks are substantially similar.

Once the prerequisites for a dilution claim are satisfied, the owner of a mark can bring an action against any use of that mark that dilutes the distinctive quality of that mark, either through “blurring” or “tarnishment” of that mark; Tarnishment occurs when the mark is cast in an unflattering light, typically through its association with inferior or unseemly products or services. So, for example, in a recent case, ToysRUs successfully brought a tarnishment claim against adultsrus.com, a pornographic website.

Remedies for Trademark Infringement and/or Dilution

Successful plaintiffs are entitled to a wide range of remedies under federal law. Such plaintiffs are routinely awarded injunctions against further infringing or diluting the use of the trademark. In trademark infringement suits, monetary relief may also be available, including:

(1) Defendant’s profits,

(2) Damages sustained by the plaintiff, and

(3) The costs of the action.

Damages may be trebled upon showing bad faith. In trademark dilution suits, however, damages are available only if the defendant willfully traded on the plaintiff’s goodwill in using the mark. Otherwise, plaintiffs in a dilution action are limited to injunctive relief. (HG.org, 2016)

Bibliography

Harms, D. K. (2014). Federal and State Trademark Registration. Del Mar, CA: American Patent and Trademark Law Center.

HG.org. (2016). Trademark Law. HG.org: Legal resources. Retrieved from https://www.hg.org/trademark-law.html

LII. (2015). Trademark. Legal Information Institute. Retrieved from https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/trademark

Tysver, D. A. (2015). COMMON LAW TRADEMARK RIGHTS. BITLAW.

USPTO. (2016). Trademark Basics: Basic Facts About Trademarks: What Every Small Business Should Know Now, Not Later. USPTO. Retrieved from http://www.uspto.gov/trademarks-getting-started/trademark-basics

WIPO. (2015). U.S. Trademark Law: Rules of Practice in Trademark Cases, 37 C.F.R. 2 et seq. & Federal Statues; Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1051 et seq. & Patent Act, 35 U.S.C. Part 1 (Consolidated Trademark Law and Regulation as of July 11, 2015). World Intellectual property organization.